What are terrariums? Part II

In an earlier post, we talked about Wardian cases and the beginnings of the answer to What is a terrarium?. We discussed how a terrarium is something of a controlled ecosystem. Ideally, that ecosystem closely replicates the natural environmental conditions of the plants, and sometimes animals, which live in them.

In an earlier post, we talked about Wardian cases and the beginnings of the answer to What is a terrarium?. We discussed how a terrarium is something of a controlled ecosystem. Ideally, that ecosystem closely replicates the natural environmental conditions of the plants, and sometimes animals, which live in them.

The key to Dr. Ward’s failed experiment was that while the moth never emerged from its chrysalis, his ecosystem was exactly what some grasses and a fern required to thrive. We already talked about how the moisture in his jar went through a natural evaporation and condensation cycle, much like the morning dew shown on this plant. But, it is so much more than moisture and humidity that defines what a terrarium is.

Making a Terrarium is About Climate Control

Dr. Ward spent years studying how plants and animals could be grown in glass cases. One of the most important things he learned was that plants typically do better when placed in a climate much like their natural habitats. Seems obvious today, but it wasn’t back then. One of his exciting discoveries was that by putting winter snow in a terrarium filled with Alpine plants, those plants more vigorously bloomed the following spring than they had in previous years.

Most of the ideal terrarium plants have two things in common – low growth rates and tropical origins. Tropical plants, used to a warm and moist climate, are a great choice for terrariums because most household temperatures are so similar to their natural habitats. They also don’t require full sun. Sun plus closed terrarium yields green, smelly soup. (Trust me, I know. Been there done that.)

Moisture Control

While I was reading about the Alpine plants, I cringed when Dr. Ward said he dumped a bunch of snow on his plants. I expected them to die from an excess of water. After all, you put too much moisture in a terrarium and everything rots.

The glass enclosures were set up much like greenhouses – with openings to allow moisture and heat escape.

The goal is for the moisture to be at the perfect level where you don’t need to fiddle with things. I can tell you I’m on day 2 of my terrarium experiment and I know for sure, mine’s too wet. The leaves are wet, the sides are wet and there’s a bit of standing water on the bottom of the jar. The lid is off and I even wiped some of the condensation off the walls of my jar. And with a bit of wiggling, I slid a turkey baster down the side of the jar and was able to suck up some of the water on the bottom. I believe I know exactly what I did wrong, but more on that later.

The goal is for the moisture to be at the perfect level where you don’t need to fiddle with things. I can tell you I’m on day 2 of my terrarium experiment and I know for sure, mine’s too wet. The leaves are wet, the sides are wet and there’s a bit of standing water on the bottom of the jar. The lid is off and I even wiped some of the condensation off the walls of my jar. And with a bit of wiggling, I slid a turkey baster down the side of the jar and was able to suck up some of the water on the bottom. I believe I know exactly what I did wrong, but more on that later.

Temperature Control

If your terrarium is housing only tropical plants, pretty much any heated and cooled room in the house should provide the ideal temperatures.

However, if you have succulents or cold-blooded reptiles living in your ecosystem, you will probably need an additional source of heat to keep everything thriving.

Like with Like

Succulents like a warm and fairly dry climate with lots of sunshine. Tropical/house plants like a slightly cooler and moister climate with natural, indirect light. Garden plants like lots of sunshine and variable amounts of water. People are mixing and matching plants that require drastically different climates and then are perplexed when their terrariums fail. My best advice would be to research the plants you have and if their growing requirements differ too greatly to either make several smaller terrariums or leave some out.

Succulents like a warm and fairly dry climate with lots of sunshine. Tropical/house plants like a slightly cooler and moister climate with natural, indirect light. Garden plants like lots of sunshine and variable amounts of water. People are mixing and matching plants that require drastically different climates and then are perplexed when their terrariums fail. My best advice would be to research the plants you have and if their growing requirements differ too greatly to either make several smaller terrariums or leave some out.

For the most part, I’m working with tropical plants. If you would like more information on building a terrarium with succulents and air plants – check out How To… Air Plant And Succulent Terrariums: 2nd Edition – Completely Revised. It’s available on Amazon.com.

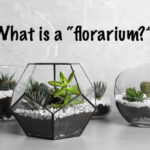

What are terrariums?

Perhaps the best answer to the question “What are terrariums?” should be edited slightly to: a terrarium is a controlled and managed ecosystem that recreates the natural environment of the plants and/or animals living inside it.